NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

What Fossil Plants Reveal About Climate Change

Paleobiologists use fossil plants to reconstruct Earth’s past climate and inform climate change research today.

In a world obsessed with human ingenuity, plants are perhaps the most underappreciated innovators. Their ability to adapt sprouts from necessity. Plants cannot root elsewhere when faced with an inhospitable environment.

“Plants are the masters of taking what’s available and using it to their advantage,” said Rich Barclay, a research geologist in the paleobiology department at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

In each habitat, these crafty inventors have evolved different characteristics to help them survive. Over millions of years, plants have left behind evidence of those characteristics in the fossil record. Paleobiologists can study this record to learn more about plants, their surrounding environments and how those environments changed over time.

Using part of the museum’s collection of 7.2 million plant fossils, Barclay and Scott Wing, a research geologist and curator of paleobotany at the museum, are uncovering clues about periods of past climate change. What they’re finding will help scientists grasp the full scale of today’s shifting climate.

“If we can interpret plants’ changes over time, we can get a sense of what past climates were like and how they changed,” said Barclay.

Fossil leaves as climate keys

When studying the museum’s collection of plant fossils for information about the climate, Wing and Barclay start with plant leaves.

Typically, plants in warmer climates have larger leaves with smoother edges, while plants in cooler climates have smaller leaves with more jagged edges.

“If I have an assortment of fossil leaves from one place, I can get an idea of what the temperature was from the proportion of species with smooth edges,” said Wing.

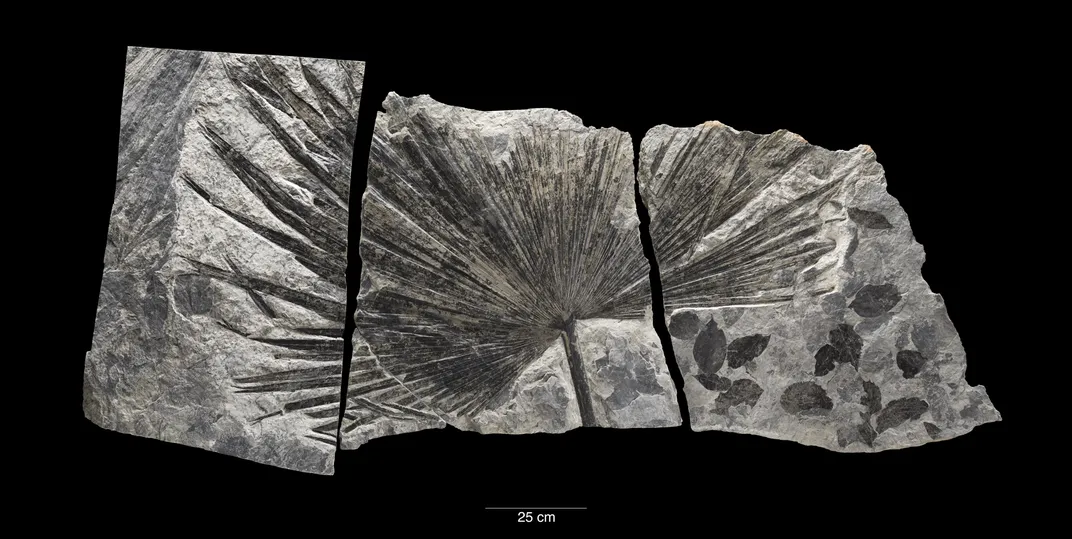

By comparing fossil plants with their modern-day relatives, Wing and Barclay can deduce what type of climate the plants were living in. For example, palm trees today are exclusively tropical or subtropical plants. So, the duo can infer that a fossilized palm likely grew in a warm climate.

“It’s like if you find a fossilized polar bear. I don’t know exactly what the climate was like back then but the fact that there’s a polar bear is a pretty strong indication that it was cold,” Wing said.

Imprints of ancient ecosystems

Roughly 56 million years ago, during a time called the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), Earth’s average temperature rose four to eight degrees Celsius in less than 10,000 years. The cause was geologic processes releasing trillions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The dramatic shift in global climate forced massive upheaval in ecosystems around the world.

“It’s the best analogue for the climate change we’re experiencing today,” Barclay said.

Fossil plants and their leaves from the PETM show that ecosystems shifted massively because of the rapid increase in global temperature. But global warming during the PETM did not come from humans. So, scientists today are working on ways to extrapolate information from that period and apply it to the even faster and more drastic events of today.

Old plants, new ideas

The National Museum of Natural History’s fossil plant collection is helping paleobiologists learn more about past climate so they can help develop a better understanding of current and future climate change.

“We use the fossils to tell us what climate was like a long time ago. Then climatologists run computer simulations of past climate. We can then compare the simulation results against the reconstructed climate to see if they agree,” said Wing.

If a modern climate model can forecast extreme past events like the PETM successfully, then it is more likely to give accurate predictions on how the planet will respond to climate change today.

“Paleobotanists are citizens of the world,” said Barclay. “We are worried about what’s going on.”

The Evolving Climate series continues May 6 when we’ll show you how researchers in the museum’s botany department use the U.S. National Herbarium’s 5 million plant specimens to study how plants have adapted to changing climates over time.

Evolving Climate: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is an organization dedicated to understanding how the past informs the present and future. Once a week, we will show you how the National Museum of Natural History’s seven scientific research departments take lessons from past climate change and apply them to the 21st century and beyond.

Related stories:

Bison Mummies Help Scientists Ruminate on Ancient Climate

What a 1000-Year-Old Seal Skull Can Say About Climate Change

Get to Know the Scientist Reconstructing Past Ocean Temperatures

Here’s How Scientists Reconstruct Earth’s Past Climates

Can You Help Us Clear the Fossil Air?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Fossil_leaves_in_rock_on_black_background.jpg)