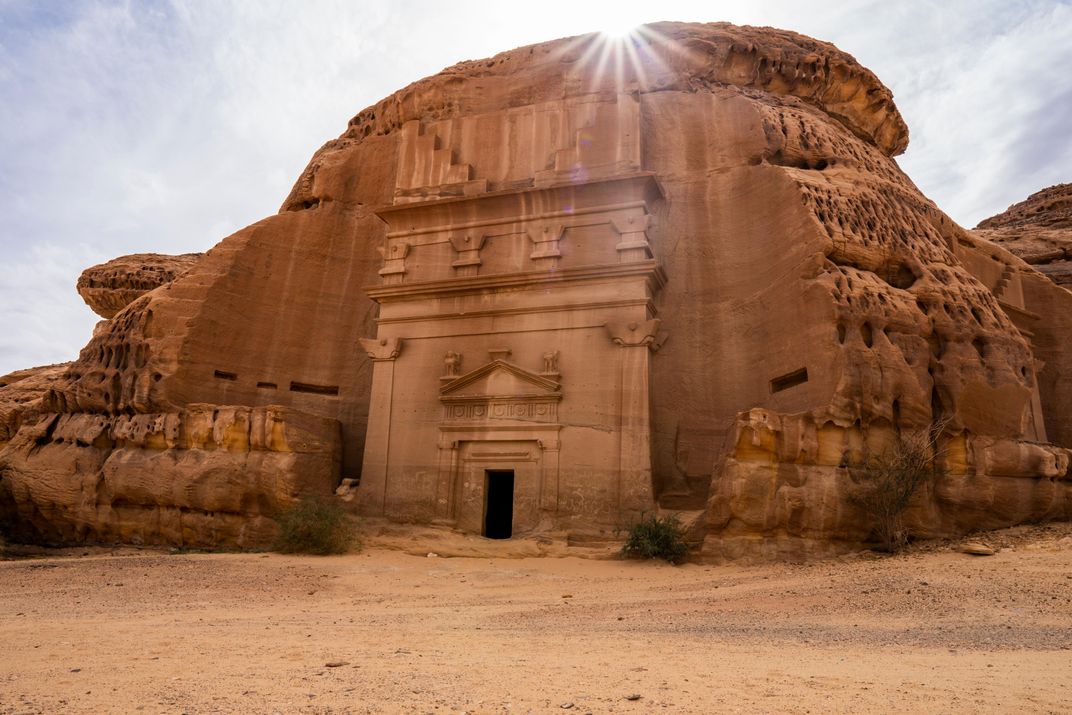

In the scrub-speckled desert north of AlUla in Saudi Arabia, rocky outcrops and giant boulders the size of buildings, beautifully carved and with classical-style pediments and columns, poke out of the sands like divinely scattered seeds. As the sun sets, the dusty colors flare, revealing pockmarks and stains caused by rain, which has shaped these stones for millennia.

Once a thriving international trade hub, the archeological site of Hegra (also known as Mada'in Saleh) has been left practically undisturbed for almost 2,000 years. But now for the first time, Saudi Arabia has opened the site to tourists. Astute visitors will notice that the rock-cut constructions at Hegra look similar to its more famous sister site of Petra, a few hundred miles to the north in Jordan. Hegra was the second city of the Nabataean kingdom, but Hegra does much more than simply play second fiddle to Petra: it could hold the key to unlocking the secrets of an almost-forgotten ancient civilization.

Determined to wean its economy off the petro pipeline, Saudi Arabia is banking on tourism as a new source of income. Oil currently accounts for 90 percent of the country’s export earnings and makes up about 40 percent of its GDP. In 2016, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced Saudi Vision 2030, a roadmap for the country over the next two decades that aims to transform it into a global hub for trade and tourism that connects Africa, Asia and Europe.

Saudi Arabia launched tourist visas for the first time in September 2019, allowing casual visitors without a business or religious purpose into the country. Hegra, with its mysterious, eye-catching architecture, is an obvious choice to highlight when marketing Saudi Arabia to tourists. Much of Hegra’s appeal lies in the fact that it’s virtually unknown to outsiders despite its similarities to Petra, which now sees nearly one million visitors a year and could be classified as an endangered world heritage site if not properly cared for, according to Unesco.

While Hegra is being promoted to tourists for the first time, the story that still seems to get lost is that of the ancient empire responsible for its existence. The Nabataeans are arguably one of the most enigmatic and intriguing civilizations that many have never heard of before.

“For a tourist going to Hegra, you need to know more than seeing the tombs and the inscriptions and then coming away without knowing who produced them and when,” says David Graf, a Nabataean specialist, archeologist and professor at the University of Miami. “It should evoke in any good tourist with any kind of intellectual curiosity: who produced these tombs? Who are the people who created Hegra? Where did they come from? How long were they here? To have the context of Hegra is very important.”

The Nabataeans were desert-dwelling nomads turned master merchants, controlling the incense and spice trade routes through Arabia and Jordan to the Mediterranean, Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia. Camel-drawn caravans laden with piles of fragrant peppercorn, ginger root, sugar and cotton passed through Hegra, a provincial city on the kingdom’s southern frontier. The Nabataeans also became the suppliers of aromatics, such as frankincense and myrrh, that were highly prized in religious ceremonies.

“The reason why they emerged and they became new in ancient sources is that they became wealthy,” says Laila Nehmé, an archeologist and co-director of the Hegra Archeological Project, a partnership between the French and Saudi governments that is excavating sections of the site. “When you become wealthy, you become visible.”

The Nabataeans prospered from the 4th century B.C. until the 1st century A.D., when the expanding Roman Empire annexed and subsumed their huge swath of land, which included modern-day Jordan, Egypt’s Sinai peninsula, and parts of Saudi Arabia, Israel and Syria. Gradually, the Nabataean identity was lost entirely. Forgotten by the West for centuries, Petra was “rediscovered” by Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812, though local Bedouin tribes had been living in the caves and tombs for generations. Perhaps it could be said that Petra was truly seen by most Westerners for the first time a century and a half later thanks to its starring role as the set for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade in 1989.

The challenge with getting to know the Nabataeans is that they left behind so little first-hand history. With the immense popularity of Petra today, it’s hard to imagine that we don’t know much about its creators. Most of what we’ve learned about the Nabataeans comes from the documents of outsiders: the ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians.

“The reason we don’t know much about them is because we don’t have books or sources written by them that tell us about the way they lived and died and worshipped their gods,” says Nehmé. “We have some sources that are external, so people who talk about them. They did not leave any large mythological texts like the ones we have for Gilgamesh and Mesopotamia. We don’t have their mythology.”

Like Petra, Hegra is a metropolis turned necropolis: most of the remaining structures that can be seen today are tombs, with much of the architectural remains of the city waiting to be excavated or already lost, quite literally, to the sands of time. One of the only places where the words of the Nabataeans exist is in the inscriptions above the entrances to several of the tombs at Hegra.

Obscure though they might be to us now, the Nabataeans were ancient pioneers in architecture and hydraulics, harnessing the unforgiving desert environment to their benefit. Rainwater that poured down from the craggy mountains was collected for later use in ground-level cisterns. Natural water pipes were built around the tombs to protect their facades from erosion, which have kept them well preserved thousands of years after their construction.

“These people were creative, innovative, imaginative, pioneering,” says Graf, who has been researching the Nabataeans since he unexpectedly unearthed some of their pottery in 1980 on an excavation in Jordan. “It just blew my mind.”

Hegra contains 111 carefully carved tombs, far fewer than the more than 600 at the Nabataean capital of Petra. But the tombs at Hegra are often in much better condition, allowing visitors to get a closer look into the forgotten civilization. Classical Greek and Roman architecture clearly influenced construction, and many tombs include capital-topped columns that hold a triangular pediment above the doorway or a tomb-wide entablature. A Nabataean “crown,” consisting of two sets of five stairs, rests at the uppermost part of the facade, waiting to transport the soul to heaven. Sphinxes, eagles and griffins with spread wings—important symbols in the Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Persian worlds—menacingly hover above the tomb entrances to protect them from intruders. Others are guarded by Medusa-like masks, with snakes spiraling out as hair.

Nehmé calls this style Arab Baroque. “Why Baroque? Because it is a mixture of influences: we have some Mesopotamian, Iranian, Greek, Egyptian,” she says. “You can borrow something completely from a civilization and try to reproduce it, which is not what they did. They borrowed from various places and built their own original models.”

Intimidating inscriptions, common on many of the tombs at Hegra but rare at Petra, are etched into the facade and warn of fines and divine punishment for trespassing or attempting to surreptitiously occupy the tomb as your own. “May the lord of the world curse upon anyone who disturb this tomb or open it,” proclaims part of the inscription on Tomb 41, “...and further curse upon whoever may change the scripts on top of the tomb.”

The inscriptions, written in a precursor to modern Arabic, sometimes read as jumbled legalese, but a significant number include dates—a gold mine for archeologists and historians. Hegra’s oldest dated tomb is from 1 B.C. and the most recent from 70 A.D., allowing researchers to fill in gaps on the Nabataeans’ timeline, though building a clear picture is still problematic.

Graf says that about 7,000 Nabataean inscriptions have been found throughout their kingdom. “Out of that 7,000, only a little over 100 of them have dates. Most of them are very brief graffiti: the name of an individual and his father or a petition to a god. They are limited in their content, so it’s difficult to write a history on the basis of the inscriptions.”

Some tombs at Hegra are the final resting places for high-ranking officers and their families, who, according to the writing on their tombs, took the adopted Roman military titles of prefect and centurion to the afterworld with them. The inscriptions also underscore Hegra’s commercial importance on the empire’s southern fringes, and the texts reveal the diverse composition of Nabataean society.

“I argue the word Nabataean is not an ethnic term,” Graf says. “Rather it’s a political term. It means they are the people who controlled a kingdom, a dynasty, and there are various kinds of people in the Nabataean kingdom. Hegrites, Moabites, Syrians, Jews, all kinds of people.”

The full stories behind many of these tombs remain unknown. Hegra’s largest tomb, measuring about 72 feet tall, is the monolithic Tomb of Lihyan Son of Kuza, sometimes called Qasr al-Farid, meaning the “Lonely Castle” in English, because of its distant position in relation to the other tombs. It was left unfinished, with rough, unsmoothed chisel marks skirting its lower third. A few tombs were abandoned mid-construction for unclear reasons. The deserted work at Tomb 46 shows most clearly how the Nabataeans built from top to bottom, with only the stepped “crown” visible above an uncut cliffside. Both the Tomb of Lihyan Son of Kuza and Tomb 46 have short inscriptions, designating them for specific families.

A new chapter in Hegra’s history, however, is just beginning, as travelers are allowed easy access to the site for the first time. Previously, less than 5,000 Saudis visited Hegra each year, and foreign tourists had to obtain special permission from the government to visit, which fewer than 1,000 did annually. But now it’s as simple as buying a ticket online for 95 Saudi riyal (about $25). Hop-on-hop-off buses drop visitors off in seven areas, where Al Rowah, or storytellers, help bring the necropolis to life. Tours are given in Arabic and English.

“They are tour guides, but they are more than that,” says Helen McGauran, curatorial manager at the Royal Commission for AlUla, the Saudi governing body that's the caretaker of the site. “The handpicked team of Saudi men and women have been mentored by archeologists and trained by international museums to connect every visitor to the stories of this extraordinary open-air gallery. Many are from AlUla and speak beautifully of their own connections to this place and its heritage.”

A visit to Hegra is merely scratching the surface of AlUla’s archeological trove. Other nearby heritage sites—the ancient city of Dadan, the capital of the Dadanite and Lihyanite kingdoms, which predated the Nabataeans, and Jabal Ikmah, a canyon filled with ancient rock inscriptions—are also now open to visitors. AlUla’s labyrinthine old town of mudbrick houses, which had been occupied since the 12th century but more recently abandoned and fell into a state of disrepair, is now a conservation site and is slated to welcome tourists starting in December.

“Hegra is absolutely the jewel in the crown,” McGauran says. “However, one of the beautiful and unique things about AlUla is that it is this palimpsest of human civilization for many thousands of years. You have this near continuous spread of 7,000 years of successive civilizations that are settling in this valley—important civilizations that are just now being revealed to the world through archeology.”

By 2035, AlUla is hoping to attract two million tourists (domestic and international) annually. AlUla’s airport, about 35 miles from Hegra, only opened in 2011, but it has already undergone large-scale renovations in anticipation of the influx of visitors, quadrupling its annual passenger capacity. The Pritzker Prize-winning French architect Jean Nouvel is designing a luxury cliff-carved cave hotel inspired by the Nabataeans’ work at Hegra, set to be completed in 2024.

“We see the development of AlUla as a visitor destination as being something that is happening with archeology and heritage at its heart, with a new layer of art, creativity and cultural institutions being added to that,” McGauran says.

Scholars believe that the Nabataeans saw their tombs as their eternal home, and now their spirits are being resurrected and stories retold as part of AlUla’s push to become an open-air museum.

“This is not just one museum building. This is an extraordinary landscape where heritage, nature and arts combine,” McGauran says. “We talk a lot about AlUla for millennia as being this place of cultural transfer, of journeys, of travelers, and a home to complex societies. It continues to be that place of cultural identity and artistic expression.”

Though the Nabataeans left behind scant records, Hegra is where their words are most prominently visible. But the Nabataeans weren’t the only ones here: about 10 historic languages have been found inscribed into the landscape of AlUla, and this region in particular is seen as instrumental in the development of the Arabic language. Something about AlUla has inspired civilization after civilization to leave their mark.

“Why are we telling these stories here?” McGauran asks. “Because they’re not stories that you can tell anywhere else.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/69/59691db3-ebcd-49cb-99fe-07437316e3bb/madain_saleh_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/49/09496036-521e-4452-8747-b9b07e0de15e/madain_saleh_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauren.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauren.png)