If you drive north from Khartoum along a narrow desert road toward the ancient city of Meroe, a breathtaking view emerges from beyond the mirage: dozens of steep pyramids piercing the horizon. No matter how many times you may visit, there is an awed sense of discovery. In Meroe itself, once the capital of the Kingdom of Kush, the road divides the city. To the east is the royal cemetery, packed with close to 50 sandstone and red brick pyramids of varying heights; many have broken tops, the legacy of 19th-century European looters. To the west is the royal city, which includes the ruins of a palace, a temple and a royal bath. Each structure has distinctive architecture that draws on local, Egyptian and Greco-Roman decorative tastes—evidence of Meroe’s global connections.

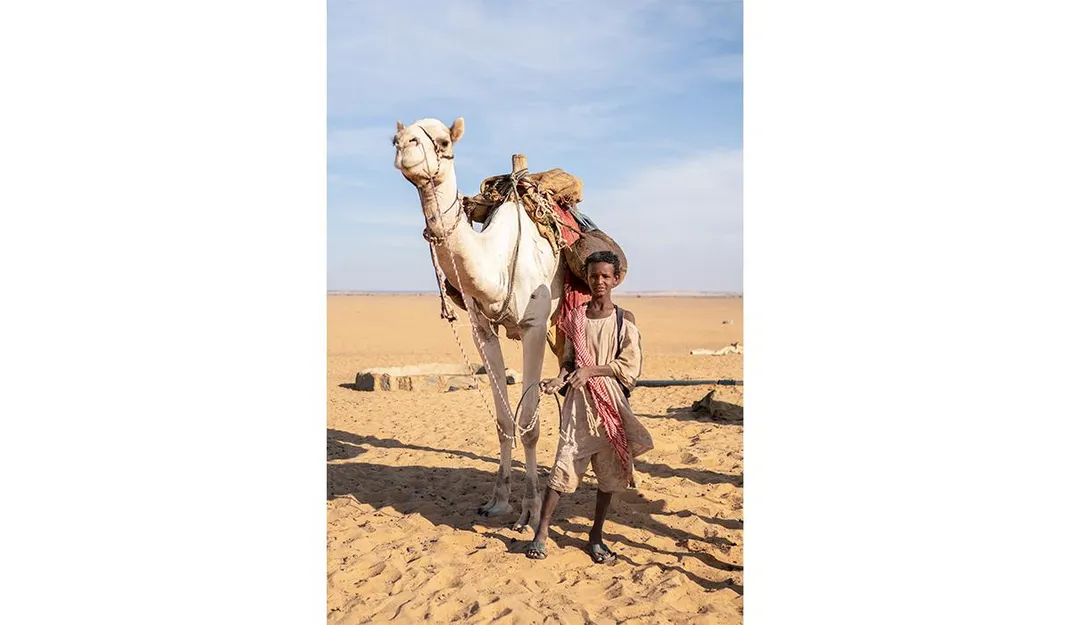

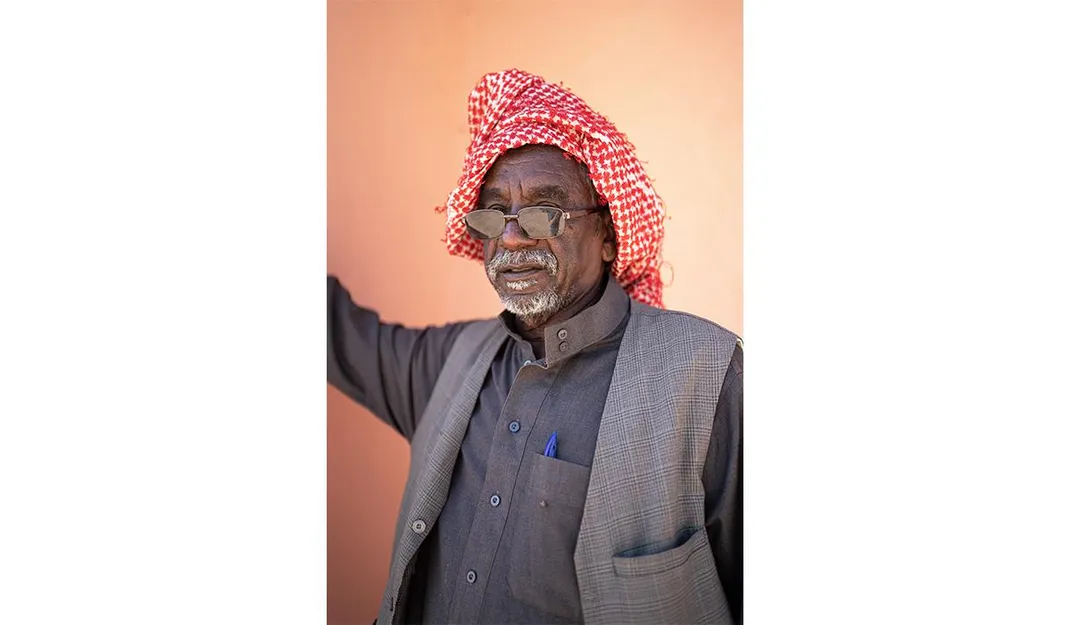

Off the highway, men wearing Sudanese jalabiyas and turbans ride camels across the desert sands. Although the area is largely free of the trappings of modern tourism, a few local merchants on straw mats in the sand sell small clay replicas of the pyramids. As you approach the royal cemetery on foot, climbing large, rippled dunes, Meroe’s pyramids, lined neatly in rows, rise as high as 100 feet toward the sky. “It’s like opening a fairytale book,” a friend once said to me.

I first learned of Sudan’s extraordinary pyramids as a boy, in the British historian Basil Davidson’s 1984 documentary series “Africa.” As a Sudanese-American who was born and raised in the United States and the Middle East, I studied the history of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Levant, Persia, Greece and Rome—but never that of ancient Nubia, the region surrounding the Nile River between Aswan in southern Egypt and Khartoum in central Sudan. Seeing the documentary pushed me to read as many books as I could about my homeland’s history, and during annual vacations with my family I spent much of my time at Khartoum’s museums, viewing ancient artifacts and temples rescued from the waters of Lake Nasser when Egypt’s Aswan High Dam was built during the 1960s and ’70s. Later, I worked as a journalist in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, for close to eight years, reporting for the New York Times and other news outlets about Sudan’s fragile politics and wars. But every once in a while I got to write about Sudan’s rich and relatively little known ancient history. It took me more than 25 years to see the pyramids in person, but when I finally visited Meroe, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of fulfilled longing for this place, which had given me a sense of dignity and a connection to global history. Like a long lost relative, I wrapped my arms around a pyramid in a hug.

The land south of Egypt, beyond the first cataract of the Nile, was known to the ancient world by many names: Ta-Seti, or Land of the Bow, so named because the inhabitants were expert archers; Ta-Nehesi, or Land of Copper; Ethiopia, or Land of Burnt Faces, from the Greek; Nubia, possibly derived from an ancient Egyptian word for gold, which was plentiful; and Kush, the kingdom that dominated the region between roughly 2500 B.C. and A.D. 300. In some religious traditions, Kush was linked to the biblical Cush, son of Ham and grandson of Noah, whose descendants inhabited northeast Africa.

For years, European and American historians and archaeologists viewed ancient Kush through the lens of their own prejudices and that of the times. In the early 20th century, the Harvard Egyptologist George Reisner, on viewing the ruins of the Nubian settlement of Kerma, declared the site an Egyptian outpost. “The native negroid race had never developed either its trade or any industry worthy of mention, and owed their cultural position to the Egyptian immigrants and to the imported Egyptian civilization,” he wrote in an October 1918 bulletin for Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. It wasn’t until mid-century that sustained excavation and archaeology revealed the truth: Kerma, which dated to as early as 3000 B.C., was the first capital of a powerful indigenous kingdom that expanded to encompass the land between the first cataract of the Nile in the north and the fourth cataract in the south. The kingdom rivaled and at times overtook Egypt. This first Kushite kingdom traded in ivory, gold, bronze, ebony and slaves with neighboring states such as Egypt and ancient Punt, along the Red Sea to the east, and it became famous for its blue glazed pottery and finely polished, tulip-shaped red-brown ceramics.

Among those who first challenged the received wisdom from Reisner was the Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet. It took 20 years for Egyptologists to accept his argument. “Western archaeologists, including Reisner, were trying to find Egypt in Sudan, not Sudan in Sudan,” Bonnet told me. Now 87, Bonnet has returned to Kerma to conduct field research every year since 1970, and has made several significant discoveries that have helped rewrite the region’s ancient history. He identified and excavated a fortified Kushite metropolis nearby, known as Dukki Gel, which dates to the second millennium B.C.

Around 1500 B.C., Egypt’s pharaohs marched south along the Nile and, after conquering Kerma, established forts and temples, bringing Egyptian culture and religion into Nubia. Near the fourth cataract, the Egyptians built a holy temple at Jebel Barkal, a small flat-topped mountain uniquely situated where the Nile turns southward before turning northward again, forming the letter “S.” It was this place, where the sun is born from the “west” bank—typically associated with sunset and death—that ancient Egyptians believed was the source of Creation.

Egyptian rule prevailed in Kush until the 11th century B.C. As Egypt retreated, its empire weakening, a new dynasty of Kushite kings rose in the city of Napata, about 120 miles southeast of Kerma, and asserted itself as the rightful inheritor and protector of ancient Egyptian religion. Piye, Napata’s third king, known more commonly in Sudan as Piankhi, marched north with an army that included horsemen and skilled archers and naval forces that sailed north on the Nile. Defeating a coalition of Egyptian princes, Piye established Egypt’s 25th Dynasty, whose kings are commonly known as the Black Pharaohs. Piye recorded his victory in a 159-line inscription in Middle Egyptian hieroglyphics on a stele of dark gray granite preserved today in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. He then returned to Napata to rule his newly expanded kingdom, where he revived the Egyptian tradition, which had been dormant for centuries, of entombing kings in pyramids, at a site called El-Kurru.

One of Piye’s sons, Taharqa, known in Sudan as Tirhaka, was mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as an ally of Jerusalem’s King Hezekiah. He moved the royal cemetery to Nuri, 14 miles away, and had a pyramid built for himself that is the largest of those erected to honor the Kushite kings. Archaeologists still debate why he moved the royal cemetery. Geoff Emberling, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan who has excavated at El-Kurru and Jebel Barkal, told me that one explanation focusing on Kushite ritual is that Taharqa situated his tomb so that “the sun rose over the pyramid at the moment when the Nile flooding is supposed to have arrived.” But there are other explanations. “There might have been a political split,” he said. “Both explanations might be true.”

The Black Pharaohs’ rule of Egypt lasted for nearly a century, but Taharqa lost control of Egypt to invading Assyrians. Beginning in the sixth century B.C., when Napata was repeatedly threatened by attack from Egyptians, Persians and Romans, the kings of Kush gradually moved their capital south to Meroe. The city, at the junction of several important trade routes in a region rich in iron and other precious metals, became a bridge between Africa and the Mediterranean, and it grew prosperous. “They took on influences from outside—Egyptian influences, Greco-Roman influences, but also influences from Africa. And they formed their very own ideas, their own architecture and arts,” says Arnulf Schlüter, of the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich.

The pyramids in Meroe, which was named a Unesco World Heritage site in 2011, are undoubtedly the most striking feature here. While they are not as old or as large as the pyramids in Egypt, they are unique in that they are steeper, and they were not all dedicated to royals; nobles (at least those who could afford it) came to be buried in pyramids as well. Many Sudanese today are quick to point out that the number of standing ancient pyramids in the country—more than 200—exceeds the number of those in Egypt.

Across from the pyramids is the royal city, with surrounding grounds that are still covered in slag, evidence of the city’s large iron-smelting industry and a source of its economic power. Queens called by the title Kandake, known in Latin as “Candace,” played a vital role in Meroitic political life. The most famous of them was Amanirenas, a warrior-queen who ruled Kush from roughly 40 B.C. to 10 B.C. Described by the Greek geographer Strabo, who mistook her title for her name, as “a masculine sort of woman, and blind in one eye,” she led an army to fight off the Romans to the north and returned with a bronze statue head of Emperor Augustus, which she then buried in Meroe beneath the steps to a temple dedicated to victory. In the town of Naga, where Schlüter does much of his work, another kandake, Amanitore, who ruled from about 1 B.C. to A.D. 25, is portrayed beside her co-regent, King Natakamani, on the entrance-gate wall of a temple dedicated to the indigenous lion god Apedemak; they are depicted slaying their enemies—Amanitore with a long sword, Natakamani with a battle-ax—while lions rest symbolically at their feet. Many scholars believe that Amanitore’s successor, Amantitere, is the Kushite queen referred to as “Candace, queen of the Ethiopians” in the New Testament, whose treasurer converted to Christianity and traveled to Jerusalem to worship.

At another site not far away, Musawwarat es-Sufra, archaeologists still wonder about the purpose that a large central sandstone complex, known as the Great Enclosure, might have served. It dates to the third century B.C., and includes columns, gardens, ramps and courtyards. Some scholars have theorized that it was a temple, others a palace or a university, or even a camp to train elephants for use in battle, because of the elephant statues and engravings found throughout the complex. There is nothing in the Nile Valley to compare it to.

By the fourth century A.D., the power of Kush began to wane. Historians give different explanations for this, including climate change-driven drought and famine and the rise of a rival civilization in the east, Aksum, in modern-day Ethiopia.

For years, Kush’s history and contributions to world civilization were largely ignored. Early European archaeologists were unable to see it as more than a reflection of Egypt. Political instability, neglect and underdevelopment in Sudan prevented adequate research into the country’s ancient history. Yet the legacy of Kush is important because of its distinctive cultural achievements and civilization: it had its own language and script; an economy based on trade and skilled work; a well-known expertise in archery; an agricultural model that allowed for raising cattle; and a distinctive cuisine featuring foods that reflected the local environment, such as milk, millet and dates. It was a society organized differently from its neighbors in Egypt, the Levant and Mesopotamia, with unique city planning and powerful female royals. “At its height, the Kingdom of Kush was a dominant regional power,” says Zeinab Badawi, a distinguished British-Sudanese journalist whose documentary series “The History of Africa” aired on the BBC earlier this year. Kush’s surviving archaeological remains “reveal a fascinating and uncelebrated ancient people the world has forgotten.”

While Egypt has long been explained in light of its connections to the Near East and the Mediterranean, Kush makes clear the role that black Africans played in an interconnected ancient world. Kush was “at the root of black African civilizations, and for a long time scholars and the general public berated its achievements,” Geoff Emberling told me. Edmund Barry Gaither, an American educator and director of Boston’s Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, says that “Nubia gave black people their own place at the table, even if it did not banish racist detractors.” The French archaeologist Claude Rilly put it to me this way: “Just as Europeans look at ancient Greece symbolically as their father or mother, Africans can look at Kush as their great ancestor.”

Today, many do. In Sudan, where 30 years of authoritarian rule ended in 2019 after months of popular protests, a new generation is looking to their history to find national pride. Among the most popular chants by protesters were those invoking Kushite rulers of millennia past: “My grandfather is Tirhaka! My grandmother is a Kandake!”

Intisar Soghayroun, an archaeologist and a member of Sudan’s transitional government, says that rediscovering the country’s ancient roots helped fuel the calls for change. “The people were frustrated with the present, so they started looking into their past,” she told me. “That was the moment of revolution.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/20/e0209c87-867d-461a-976c-4102f944b9fa/sudanopener_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/20/1b205e98-4c95-4d82-a053-5bc6e8d34c65/sudan_opener_socialmedia.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/53/1653c9b6-6263-4e8e-ae35-8f9a63d7b2ec/medina_a_97_year_old_hassania_nomad_sits_in_her_tent_in_the_remote_bayuda_desert.jpg)