NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

How Film Helps Preserve the World’s Diversity

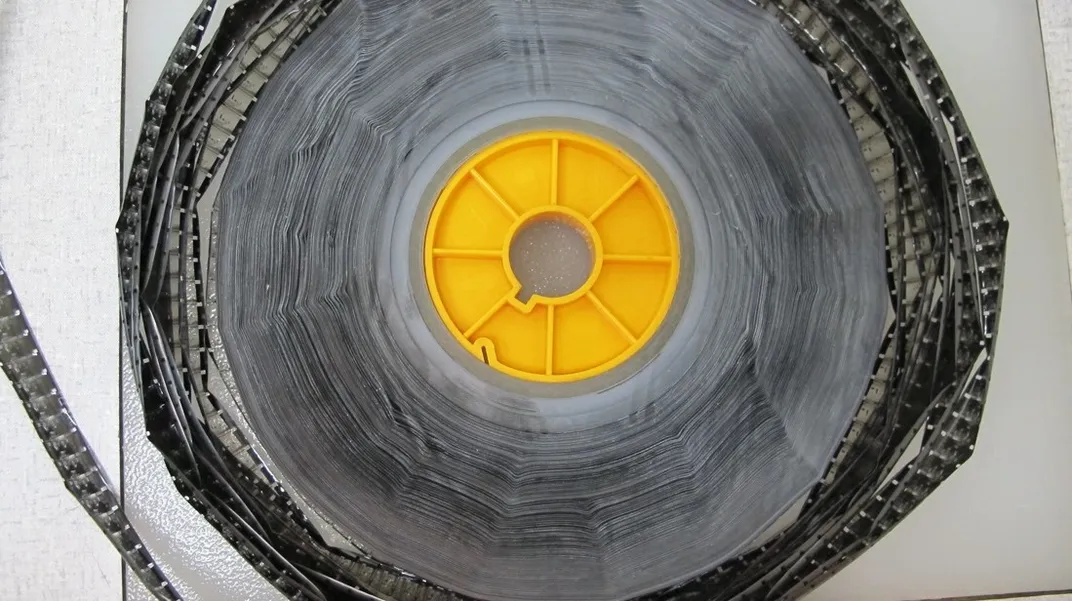

The Smithsonian’s Human Studies Film Archive houses eight million feet of film which can help future generations reflect on the past.

The term “filmmaking” evokes Hollywood glamor and opulent backdrops. But it also has an important place in anthropology, as one of the many tools and technologies these scientists use to understand communities, relationships, cultures and history.

During the Smithsonian’s annual Mother Tongue Film Festival, anthropological filmmaking and digital storytelling take centerstage in the Festival’s exploration of the healing power of language and storytelling.

“We try to find meaning in what people themselves do and say. It’s about understanding the way of life, its particular conditions, its manifestations, its concerns and its meanings,” said Dr. Ákos Östör, a filmmaker-anthropologist at Wesleyan University.

He and Dr. Lina Fruzzetti, a filmmaker-anthropologist at Brown University, are co-creators of six of the Festival’s films. Recently, they donated nine ethnographic films to the National Museum of Natural History’s Human Studies Film Archives (HSFA) — a film collection within the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) that is maintained for future generations to learn more about people across the world and their global history.

“This is a moving, visual archive of the world and one way in which we further the preservation of the world’s diversity for communities and researchers,” said Dr. Joshua Bell, curator of globalization, co-director of the festival and acting director of the National Anthropological Archives at the museum.

From window to door

Anthropological films will always have a home in the National Museum of Natural History’s Human Studies Film Archive, because they combine research with lived experience.

“There is nothing like film to convey the rich complexity of other people’s lives outside of meeting them. The medium transports people and moves them. It’s very powerful,” said Bell.

Through visual ethnography, anthropologists strive to document social dynamics and traditions. But the field has nuances. For example, filming can change how people interact with each other. It might make them censor their words and their emotions. Over time, anthropologists have adapted to this, and have come to embrace their roles as active participants in the filmmaking.

"It's shifted from using the camera as a window into a world and instead anthropologists now use the camera as a door that people can walk through. The creating process is much more dialogical,” said Bell.

But even though past films were partial “windows” into societies and were shaped by preoccupations of the filmmakers, they still hold value for anthropologists seeking to contextualize the discipline, and for communities themselves seeking to understand their history.

“Film is always a snapshot in time. It has content, but it also reflects an attitude. We can use it when we want to look back on how we were showing our world,” said Pam Wintle, the senior film archivist at the museum’s National Anthropological Archives.

Since the late 60s, ethnographic filmmaking has been confronting its colonial origins and moving beyond it. The field now works with communities in partnerships rather than exoticizing them. Anthropologists like Fruzzetti and Östör recognize that cultivating long-term, trust-based relationships is crucial before any camerawork can begin.

"Unless you’ve done the prior work, you really have no clue of how to portray a community, what they value and what it means to them,” said Fruzzetti.

A 30-year ethnographic legacy

Fruzzetti and Östör first began working together over 30 years ago. Their most recent film, “In My Mother’s House,” was made in 2017 and unravels Fruzzetti’s family history within the context of Italian colonialism in Eritrea.

“I knew that my mother has an incredible story, and it isn’t just for me. It goes beyond one family and will reach a much wider audience,” said Fruzzetti. The team called the film a “total departure” from anything they’ve done before.

“It’s a very lowkey, gentle unfolding of a history that starts to resonate with everybody’s history as they learn about their family, their history and their culture. It draws you into her story in the film,” said Wintle.

Five other films by Fruzzetti and Östör will also be streaming at the Mother Tongue Film Festival as part of a retrospective of their work. Titles include “Seed and Earth,” “Khalfan and Zanzibar,” “Fishers of Dar,” “Singing Pictures” and “Songs of A Sorrowful Man.”

Now the team’s decades-long collaboration of films, field notes and raw footage reside at the Human Studies Film Archive where they will be accessible to everyone.

"Our field notes, drafts, photographs, videos, publications and films are all there for the archive to bring into the lives of contemporary society and institutions as something vitally involved in the past, present and future,” said Östör.

Films for the future

The Human Studies Film Archives is a subset of the museum’s National Anthropological Archives and holds films spanning more than a century.

“What’s unique about the HSFA is that it is the largest film archive devoted to anthropological films in the world. I think about it as the sleeping giant at the Smithsonian because it has over eight million feet of film and it spans the globe in terms of focus and material,” said Bell.

Those eight million feet of film are not only limited to ethnographic footage. The archive also stores amateur films and travelogues as well, all of which can help future generations reflect on the past.

“Our collection comes from anthropology, history, ethnography and film studies, which is its own important area of exploration. It can reveal our understanding of our own cultural history,” said Wintle.

One of the driving goals for the archive is to make its footage accessible to all people everywhere. Anthropologists can analyze the collections to see how they depict places and people, while communities in these films can also find value in their cultural preservation.

“I've always felt this collection was really for the future. Now, future is starting to catch up with the collection because, with digitization, we can make this material accessible and available,” said Wintle.

Editor’s note: On March 19, 2021, filmmaker-anthropologists Dr. Lina Fruzzetti, at Brown University, and Dr. Ákos Östör, at Wesleyan University, will discuss the nuances of filmmaking and storytelling within the field. Until March 31, 2021, Fruzzetti and Östör’s latest jointly created film, called “In My Mother’s House,” is available for online streaming as part of the Mother Tongue Film Festival.

Related Stories:

How Arctic Anthropologists are Expanding Narratives about the North

How Ancient DNA Unearths Corn’s A-maize-ing History

What Chocolate-Drinking Jars Tell Indigenous Potters Now

Meet the Scientist Studying How Cellphones Change Societies

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Stacked_reels_and_canisters_of_film_on_gray_background.jpg)