NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

How Elaborate Cakes Make Science Sweet

Smithsonian archaeologist Eric Hollinger makes science sweet with elaborate, science-themed cakes.

Cakes are the perfect centerpiece of a celebration. Whether you’re celebrating a birthday, a wedding or National Cake Day, a sweet slice of cake makes any event special. At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, one archeologist has made cakes the highlight of the anthropology department’s annual holiday party.

For many at the museum, the cakes have become a holiday tradition that they look forward to with anticipation. But the cakes aren’t just delicious. They’re also scientifically accurate recreations of anthropological subjects that educate and delight the imagination.

A holiday tradition

In 2004, Smithsonian archaeologist Eric Hollinger had some fun preparing his contribution to the department's annual holiday potluck party. He used 14 cakes and blue Jell-O to create the scene of an archeological dig site at a Mississippian temple mound.

“It was just for fun,” says Hollinger. “But then the next year people were asking me ‘Are you doing anything? Are you making a cake?’ And I’d say 'No, I’m not making a cake.'"

He wasn’t quite lying. Hollinger didn’t want to disappoint his colleagues so he brought a chocolate longhouse he made in the style of the Haida Native American tribe instead of a cake. After that, bringing an intricate sweet became a tradition.

Every year since, Hollinger has delivered elaborate, science themed desserts. His designs come from some aspect of archeology or anthropology — except in 2010 when he celebrated the 100th anniversary of the museum by including elements from the other research departments.

“The detail and beauty of Eric’s cakes are over the top,” says Carla Dove, who manages the Smithsonian Feather Identification Lab. “It's one of the highlights of the whole season to go and try to get a peek at Eric’s cake before it's cut.”

Hollinger dedicates his free time and money to the elaborate projects. He says that the work is “kind of relaxing,” serving as a sort of “evening therapy in the fall” that pushes him to learn more. Every year, he pushes himself to do something new— not just a new subject, but often learning a new skill, using a new edible medium or pushing the scale and intricacy of the projects.

“Eric devotes evenings and weekends to making the cakes,” says Laurie Burgess, the associate chair of the anthropology department. “We don't think he sleeps, because he just cranks out so much work during the day, and then he goes home and works on the cakes.”

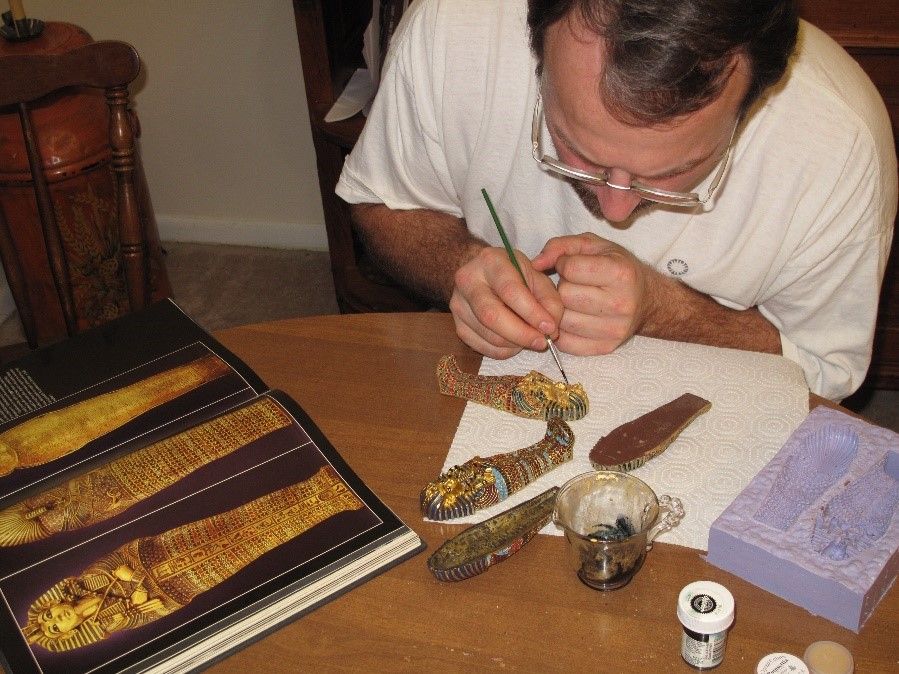

He has made an array of confectionary artworks, spanning everything from an Aztec calendar stone that he carved out of a solid block of chocolate using only a nail to a Viking ship with boards made from Kit-Kat wafers and a Tibetan mandala made using colored sugar for the intricate designs on the cake instead of the traditional colored sand.

Art meets science

Hollinger makes the cakes to both taste good and be accurate. He meticulously researches his subject matter, often consulting experts, to create a faithful depiction.

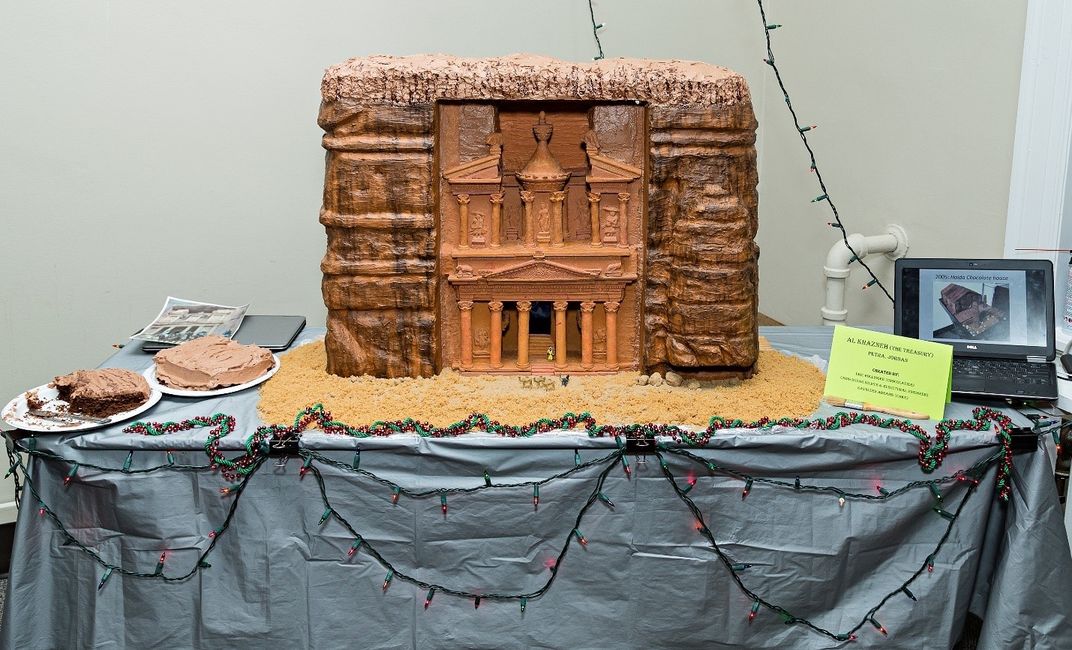

A particularly popular one of his creations was a 1-to-100 scale replica of Al Khazneh — also known as the Treasury — at Petra, Jordan. The cake captured enough detail that archeology buffs and fans of the movie “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” will likely recognize it at a glance.

"The layout, the dimensions of each of the columns, the decorations and all of that was exactly the same as it is on the actual Treasury at Petra,” says Hollinger. “We had scientists down the hall in the museum who are experts on Petra who came to the party to see it. They looked at it and said, ‘Yeah, it looks exactly like the real thing.’”

Hollinger not only put excruciating detail into the creation but also had a little extra fun. He included audio and video technology in the party cake for the first time, specifically an iPad playing a video loop of the “Indiana Jones” end scenes that took place in Al Kazneh.

Teaching with cakes and candy

The fun presentation of actual science has made this more than just a hobby and annual tradition for Hollinger. He believes that finding ways to present subjects in new, unusual ways helps many people connect more deeply than they would otherwise.

“The cakes are a lovely way of humanizing staff and putting a different spin on the amazing work we do here,” Burgess says. “It presents a human face, and it brings in the element of fun and creativity.”

Hollinger was once contacted by the mother of a girl whose class was studying the famous Chinese tomb that features an army of terracotta warriors. She had learned about his cake that featured the tomb online and thought it would be a way to help the students engage with the topic. So, he talked through the process with her and ended up mailing her the silicone molds he had made since casting 100 chocolate warriors was the most challenging step.

“When I see or hear something like that, I realize that as long as my creations are going on the web, we don't know who might be inspired to look at things in a different way and to use a different medium to make connections that they wouldn't otherwise be able to make,” Hollinger says.

A holiday surprise

While sharing the cakes is what the whole enterprise is about, Hollinger keeps the subject of each year’s cake a big secret until the party. Experts from around the world and his family and colleagues who help with the creation get to be in on the secret, but the rest of his colleagues are left guessing and eagerly awaiting the big reveal. Hollinger is already working on this year's cake and, as always, it is promising to be unique, educational and eye-catching.

If you want to see what sweet treat he has produced, make sure to keep an eye on the museum's Facebook and Twitter feeds come December 18. Even without the sugar high, it is sure to wow you and might inspire you to do a little research or baking of your own.

“Eric is so meticulous and careful with the cakes — similar to his research,” Burgess says. “It's a huge gift to the department and it's the highlight of our holiday party.”

Related stories:

Some Archaeological Dating can be as Simple as Flipping a Coin

Is 3D Technology the Key to Preserving Indigenous Cultures?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/African_Elephant.jpg)